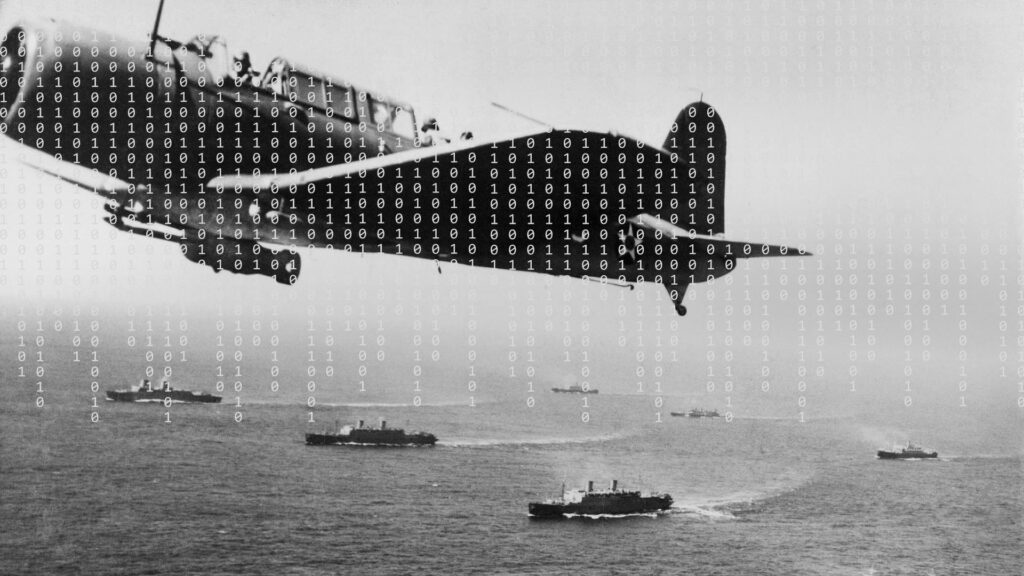

It’s hard not to feel that the world has enough articles predicting how AI will fundamentally change our lives and work, but I recently read Malcolm Gladwell’s book, The Bomber Mafia, and despite its focus being the US bombing of Japan close to 80 years ago, it was hard not to see parallels with AI:

“We live in an era when new tools and technologies and innovations emerge every day. But the only way those technologies serve some higher purpose is if a dedicated band of believers insists that they be used to that purpose…. without persistence, principles are meaningless. Because one day your dream may come true.”

The book’s themes include the ethical questions that arose from the major technological advances earlier in that century. In the book, they play out in the character and decision-making of two (real life) protagonists: General Le May and General Hansell. The first was prepared to bomb (and keep bombing) Japan with napalm after the end of the Second World War in Europe (and even after Hiroshima). The second, Hansell, remained committed to the principles behind precision-bombing (and at the expense of his career). Precision-bombing, as the name suggests, aimed to limit civilian deaths and casualties by destroying strategic/tactical enemy sites and had also been the specific motivation for some of the scientists who created the new technology.

Ultimately, the ways in which technology is designed and used as a tool is decided by people (not machines) and Gladwell’s argument is that they need to be persistent in abiding by principles when making those decisions.

Earlier this Summer, it appeared that the US company Zoom might not even have got as far as identifying first principles for the use of AI. It found itself having to defend and explain its new terms of service (TOS) which were legitimately interpreted as reserving to itself far-reaching powers over ‘customer content’ for machine learning, AI purposes – and with no option for users to ‘opt out’.

After a serious public backlash, Zoom was forced to clarify that it would not be using private audio, video or chat for this purpose. However, the question on whether it would have done so but for the backlash remains open. The TOS seemed to allow for it, and this is, after all, the company that was fined by the FTC (equivalent to the UK’s Office of Fair Trading) for wrongly claiming that it offered end-to-end encryption and for secretly installing software that made it harder for users to delete its app. It was also caught sending user data to Meta and LinkedIn.

So, what next?

The Bomber Mafia is about in part the choices that come with fundamental technological developments; in 1945, it was a choice about how to use the technological advances in warfare.

In the world of AI, there are arguably some positive signs about the choices being made. In August, OpenAI, (the research company behind ChatGPT) decided to allow website owners to to block its ‘web-crawler’ from accessing their content. As a result, a wide number of companies such as the New York Times, Bloomberg, CNN and Amazon have been able to stop OpenAI from harvesting (or ‘scraping’) their data. ‘X’ formerly Twitter has done something similar. There has obviously been serious concern for some time about breaches of intellectual property rights arising as a result of AI systems engaging in colossal levels of data-scraping. Interestingly, OpenAI began life as a non-profit research organisation; an optimist might consider that its decision reflected a reversion to its core principles. A realist might view its decision as a pre-emptive display of ‘self-regulation’ or good PR.

The reality is that our personal data is and will continue to be highly sought after. As long ago as 2006 the British Mathematician, Clive Humby, referred to it as the “new oil”, i.e., of no value in its raw form but highly valuable when refined, processed and put to use. In 2015, we saw how Facebook and Cambridge Analytica found profitable ‘use’ for it.

It is revealing (and ironic) that tech companies such as Amazon and Microsoft have warned employees not to share sensitive internal information with AI tools such as ChatGPT in case corporate confidential information is leaked. Plainly, if their corporate confidential information can be leaked in this way so can the personal data of ordinary end users such as you and me. It is of no surprise then that one of the new jobs predicted for the future is a “Personal Data Broker” – someone employed to oversee the use and exploitation of your personal data, negotiate its value and licence it for use by select companies.

Ethical Boundary Setting

But beyond trying to predict the changes AI will bring, we can – when we correctly identify it as “machine/corporate surveillance” – recognise why principles to determine how and when it is developed and used are needed. It is clear (from the example set by social media companies) that we could be waiting a very long time for governments to step in with regulation.

On that basis, organisations and their leaders need to actively identify the risks or “ethical nightmares” of emerging technology in order to determine how they will avoid them.

Developing the skills and knowledge to do this will require an increase and evolution in Ethics Roles and Digital Ethical Risk Boards in and across organisations to ensure the persistent application of the principles behind their decisions around the use of AI:

“the tools of yesterday may have required malicious intent by those who wielded them to wreak havoc but today’s tools require no such thing”… “invading people’s privacy, automating discrimination at scale, undermining democracy, putting children in harm’s way and breaching people’s trust are decidedly clear-cut. They’re ethical nightmares that pretty much everyone can agree on.”[1]

[1] How to Avoid Ethical Nightmares of Emerging Technology, Blackman R., Harvard Business Review, May 2023.